- Home

- Alice Anderson

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away Page 2

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away Read online

Page 2

I yelled, “Get out of the way, Daddy! His hand was what I was aimin’ at!”

I found my mark again, made sure Daddy was a good bit off to the side and out of range, and shot again, this time hitting FEMA head Michael Brown right between the eyes.

Daddy ripped the paper from the tree and came running back to me, waving the paper above his head in a circle like a victory flag. He wrapped me up in his long arms and took my head in his hand, practically smashing it to his bony chest.

“You’re a natural, girl. You gonna be okay.”

I fell into his chest that smelled like chocolate and gunpowder and grease, laid my hand over his heart, felt it beat.

My other hand still held that pistol, scorching hot next to my thigh, with four more story bullets ready at the waiting.

CALAMITY

I sang the names of storms. When Hurricane Katrina barreled full force like a furious auntie breaking down a locked bedroom door into Ocean Springs, Mississippi, I never imagined the complete devastation of my town as I knew it would be the least of my troubles. A storm like that hits and you think you’re going to have to go about rebuilding a life, a house, a town. What you don’t expect is that your whole life—marriage, body, soul—will be blown to such ornate shreds that you will have to, if you hope to survive, resurrect your life entire. We’d evacuated so many times that season—with each named storm. I had been singing the named storms of 2005 with Avery to the tune of the alphabet song, and knew every one.

Arlene, Bret, Cindy, Dennis, Emily, Franklin, Gert, Harvey, Irene. Irene toppled three of our trees, one of which barely missed our house. We thought ourselves lucky.

Then Jose: scot-free.

And then Katrina.

We’d entered the long, slow procession east in a last-minute mandatory evacuation when the storm turned overnight in its path and headed straight for us. What I didn’t know as I woke up blinking against harsh light in a tacky Tallahassee motel room with my sweet three lying against me—all of them sweaty, arms akimbo, their diapers puffed up with pee—was that the devastation I was about to endure wasn’t to my beloved Mississippi coast as I knew it but to my life entire.

Because this is the story of my unraveling.

* * *

Like a strange ball of ribbon dropped from the sky in a storm—random, out of control—my life unfurled in a series of disastrous, love-soaked, sometimes dazzling, sometimes devastating events marked by a doomed love, by babies born, by a once-in-a-lifetime hurricane, by brutal domestic violence, by a night of the soul so long it seemed that daylight might never come. All of it complicated by a Gothic legal battle, a traumatic brain injury, and affairs of the heart both sweetly maternal and wildly romantic.

But on this day, I was in a scratchy motel bed with three babies, and I didn’t know if I had a house or town or pot to stir in.

This is also the story of redemption found within a storm and how some things hold true, no matter what. There’s one true thing about a hurricane: it doesn’t change people, it exposes them. And yet how extraordinary circumstances led me to slip so slowly yet effortlessly, disastrously, down into the dark, silky, shameful corners of abuse over unchecked time.

Because abuse doesn’t arrive with a neon light.

A neon light flashing DIRTY, UGLY, DIRTY, UGLY.

Instead, abuse comes in an exquisitely carved box, a boxful of secrets I thought (as every abuse victim does) only I was equipped enough—special enough—to acquire, to transform.

Abuse is a secret. A pact. A seduction.

Like a hurricane, it comes without warning.

Red flags blow in the storm, always there, often ignored.

Ignored because disaster fatigue and a kind of resigned tolerance to destruction of the heart led me to ignore all the warnings.

Abuse is quiet.

Abuse is seductive.

Abuse is a fucking liar.

But this is not a story about finding myself, but of finding my way back—back from the edge of a place where who I was was nearly erased. There’s a pure white page that sits at the seat of my soul, and typed in black raised letters are the things that make me: poet, mama, woman, fighter. I walk through fire after fire, the flames threatening to burn that page at the center of my soul, to turn me to ash. This is how I fought the flames. This is how, even when I was ankle-deep in the ashes of personal tragedy, I rose.

And so I pulled myself out from under the sleeping heap of that lopsided motel bed and flipped on the TV set to see what I could see.

Most of the coverage was of New Orleans, where the levees broke. People perched on roofs they’d hacked out of, folks wading through water, pulling babies propped up in floating beer coolers, whole bridges of stunned folks from the jail wandering the expanse of a highway bridge, suddenly set another barely kind of free.

All of that was awful. I held my fingers over my mouth and watched, waiting. About five minutes of every hour of coverage focused on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. There were wide helicopter shots, showing what looked like scraped earth and ruin. Every floating Biloxi casino ripped from its moors and crashed, thrown upcoast, destroying everything in the way. The frozen chicken shipping containers in Gulfport Harbor had broken free and covered miles and miles of land with raw, now-rotting chicken carcasses. I saw the oceanfront mausoleum, the caskets ripped clean out, littering the beaches, the structure itself like one of those Connect Four children’s games where you dropped your coins in the slots, with the sunlight now streaming straight through.

I watched, desperate for a glimpse of my town. Finally, another helicopter shot flew to the east end of Biloxi and panned over the Biloxi Bay Bridge, what we locals call the Ocean Springs–Biloxi bridge, which was collapsed bit by bit, broken triangles of concrete and steel littering the bay. The newscaster said, “That looks to be the town of Ocean Springs ahead—likely more of the same destruction found there.” Then the copter shot panned back westward, without even a glimpse of my town.

It was then I noticed he was gone.

My husband, Liam, was not in the room. His bag was gone from the closet, his wallet from the table, his toiletries gathered and vanished from the bathroom counter. I found a note propped up against the little coffeemaker:

Gone back to see if I can help. Left you the car. Buy supplies.

On the lid of the coffee carafe: a Visa card.

For just a few minutes it was silent. I whispered to myself as I put some water on for tea and to make the baby a bottle: Don’t cry. Don’t cry. You ain’t got time to cry. Crying’s for pussies and cowards, and you are neither. Get it together, Alice. Get going. Generators will sell out before noon, diapers soon after. Don’t you fucking cry.

“Who you talkin’ to, Mama?” Avery asked behind me.

“I guess myself, baby.”

“You said bad words, Mama.”

“I know, shuggie, I’m sorry. It’s a bad day.”

I realized then she was standing staring at the TV, her eyes wide. She looked at me, tears filling her eyes.

“We still got our house, Mama?”

“I don’t know, baby, but I’m trying to find out. Wake up your brothers; we fixin’ to leave.”

“Okay, Mama. But you know what?” she asked, her hair a tangled mess.

“What, baby?”

“I ain’t gonna cry neither.”

We got the boys up and their diapers changed. When Avery started to open our suitcases, I stopped her. We all put on the clothes we’d had on the night before. Who knew when we’d be able to wash clothes again? What we had on the day before was fine enough. As I threw our bags out into the hall at the top of the motel stairs, my babies stood in the motel room, light coming in behind them. Aidan, just a toddler, his sandy hair brushed to the side as always, chubby brown legs in a sumo stance, smiled around the thumb he sucked, his big green eyes smiling, too. Avery, in her little cotton dress and pink rider boots with the hand-tooled butterfly detail, held one hand reflexively on her broth

ers’ hips, holding them back from running out the door, was somehow in motion even in her stillness. Her hair, wild and dark blond, was almost to her waist, her huge eyes peering out from the tiny features of her face, full of earnest concern. And Grayson, always the thinker, the quiet one, stood with his tiny head bowed, platinum hair shorn almost to his skull, eyes staring at the floor. People often confused his quiet for shy, but I knew that even at three years old, there was a world of thought behind those sky-blue eyes.

At checkout, I asked to use the computer and logged into my e-mail. There were more than twenty e-mails from family and friends asking if we’d made it. I wrote back the same to each one: Alive. Be in touch soon.

I loaded our bags into the car and headed for Home Depot, knowing it would already be a zoo. When I got there, I got the last two generators they had—huge ones, about a thousand bucks each—and a kind young man loaded them for us into the back of the Land Rover. I put down all the seats except the front and moved the baby’s car seat up by me. The other two car seats I left in the parking lot of Home Depot and drove away.

After a storm that big, all bets (and rules of law) are off.

At Costco, I filled whatever room was left in the back of the car with cases of diapers, flats of soup and chili, crackers, enormous jars of peanut butter, eight cases of bottled water. Right before I got to the checkout, I grabbed a pack of plain white men’s T-shirts and a pair of white rubber shrimper boots my size. Across the parking lot was a chain Mexican restaurant, with a field behind it where what looked like hundreds of big white electrical trucks were staged, like white Arabians all in a line, about to take off. I put Aidan on one hip, Grayson on the other, told Avery to hold my skirt, and walked to the restaurant. Inside, every table was filled with truck drivers. We stood waiting a good while for a table. Finally, a couple of guys sitting at a six top motioned us over.

“Hey—y’all can sit with us,” one said, motioning to the four empty seats at their table.

We sat down, the waitress swapping out wooden high chairs for both boys. Grayson was so tiny he was often mistaken for an infant, even though he was three. Avery sat up close to me, didn’t look at the men.

“I’m Dave, and this here’s LaRoy. Y’all from the coast?”

“Yes, sir, I got our truck loaded up and was thinking of heading back in.”

“It’s still mandatory evacuation,” LaRoy said.

“I know, but I don’t know what else to do. I got my truck loaded full up with generators and supplies, and if I leave it anywhere too long, it’s gonna get jacked.”

“Ain’t you got no husband?” LaRoy interrupted, a skeptical look on his face.

“I do, but I woke up this morning and he’s gone! Left a note on the coffeepot saying he went back to try to help. He’s a doctor.”

“Well, how’d he get in? Y’all bring two cars?”

“No, sir, just the one. I don’t know how. I don’t know anything.”

Don’t cry, don’t cry, don’t cry, crying’s for pussies and cowards.

Dave and LaRoy exchanged glances, nodded.

“That settles it; y’all going in with us, girl,” LaRoy announced. “Y’all got people once you got there?”

“Yes, sir,” I lied. I had my girlfriends and my church friends, but I’m pretty sure that’s not the “people” he meant. But I wasn’t taking a chance he’d change his mind.

“Eat up quick now—we fixin’ to leave.”

So that’s how I ended up sneaking back into the mandatory evacuation zone, my puny-in-comparison Land Rover about twentieth in a caravan of what looked to be a hundred-odd trucks. I felt like a silly little girl riding a streamer-bedecked trike in the middle of a formal funeral procession. I felt ridiculous. I felt small.

I was also born to fight, brought up on dark nights where survival was the only choice. Fight was a part of me, a reflex; I could shut down or rev up whatever resource of the soul needed to make it through hell. I had the scars to prove it.

If only I’d known what was coming, I might not have been so cocky.

We squared our bills, went out, and I pulled the Land Rover into the long line of electric trucks like a white procession into the heart of it all.

* * *

We headed west. The closer we got, the worse things looked. Across the long bridge over Mobile Bay, I saw the first hint of destruction. The seafood joints at the ends of long piers, the bars, the wholesale shrimp shacks—all gone. We kept driving. Just past Mobile, I noticed all the trees were red—a deep umber color, leaves burned off by saltwater surge. It was unfathomable how my world could be drowned and scorched at once, but that’s how destruction often goes.

As soon as we crossed the border off Alabama into Mississippi, it was hell on earth.

At Pascagoula, every building stood in ruins, roofs ripped off, doorways blown open, empty shells of structures with debris rammed up sometimes ten feet or more high against the southern walls. Most trees were down, but those that stood, mostly oaks, were free of leaves and tangled thick with every odd manner of thing—sheets and curtains, trousers, purple lengths of silver-backed insulation, fishing nets and lace tablecloths and sodden fancy great room rugs.

At the Pascagoula Bridge the caravan stopped. A guy came banging one by one on each truck driver’s window, yelling, “Back it up, half the bridge’s down, we goin’ on the wrong side over.” We all backed up probably half a mile and then slowly headed the wrong way, west, on the east-going side of the bridge. The baby slept in his car seat. Avery was next to me with Grayson in her lap. I felt like an outlaw with the kids up front like that, but they were excited; both Avery and Grayson kept standing up and pointing at each new sight to see.

I spotted up ahead a body to the side of the bridge and told the kids to sit down and close their eyes, now.

As we traveled the last few trepidatious lengths of bridge into the town of Gautier, a single tree stood next to the now-still gulf, full up entirely with enormous vultures, like a skinny old man in a too-big, shiny, black raincoat. Ahead, the electric trucks turned one by one onto the Jackson County Fairgrounds in Pascagoula, their next staging area.

Little did I know that I’d spend the better part of the next couple of years of my life at those fairgrounds.

LaRoy and Dave stopped in front of me before turning in. LaRoy hopped out, ran back, and I rolled down my window.

“Damn, it’s bad, girl. Your house far from here?” he asked.

“If I even have a house. But, no, sir, just about ten minutes up ahead. I’m going forward.”

Don’t cry, don’t cry, crying’s for pussies and cowards.

He leaned in and kissed me on the cheek then, real hard. “You come back and find me if you need me, girl, hear?”

I nodded, my mouth set in the ugly, turned-down pre-cry, stubborn line. We drove on, along Bienville Boulevard, otherwise known as Highway 49, through the undeveloped salt pine savanna woods between Gautier and Ocean Springs, now like a long, flat, endless pelt of a giant porcupine thrown down across miles of earth, the trees broken off sharply at the top like quills, burned black from salt water, devoid of green. Everything was silent. What birds remained were pushed and buried into pockets of ruin: silent, never to sing again.

We hit town, and I passed a line of Coast Guard trucks. I worried they’d stop me, but they just raised their hands in acknowledgment as I passed. As is the case in every Southern town, at the far end border of the city limits, as distant from the original downtown as could be, sat the Walmart. So that’s what I saw first, and it was half-gone, a gaping hole where the grocery side of the store used to be. There was debris everywhere—downed fridges in the middle of the road, gutters full of every known thing, all mixed up and muddy, dead dogs pushed up against curbs, their still bodies shining with oil-like fur, dark casements of formerly loved pets reposed in the sunlight like onyx sculptures. And splintered wood everywhere. Piles upon piles of it, what remained of every house that ever was, jumbled up, a

ll kinds of colors, broken, rammed up against any buildings that remained.

“No more pizza, Mama,” said Grayson.

“Look! The steeple fell down,” said Avery, eyes wide.

I made my way through the streets, driving over and around overturned cars, pieces of houses, boat halves, and deep freezes with tops blown off, bent-up bicycles and beer coolers everywhere. The beer coolers floated out of every Gulf Coast garage, rode out the storm, then sank and landed where they may when the surge went back to sea. A silence hung in the air: the trees devoid of birdsong, structures plunged into the dark, dark hush.

I turned down our street.

“Oh no, Mama,” Avery whispered. “Oh no, oh no, oh no.”

“I know, baby, I know,” I whispered. “It’ll be okay.”

Most houses were still standing on Bayou Sauvage but had been blown straight through by the storm. Our neighborhood, a single winding street, like a small peninsula, was mostly doctors and lawyers and judges, the most expensive houses in town. The homes on the left were backed up to deepwater bayou, half a mile from open gulf; the homes on the right were backed up to the Davis Bayou Area, part of Gulf Islands National Seashore, thick woods dotted with savannas and bayous and, again, about half a mile to open gulf. Every house so far: destroyed.

And then we took that slight turn in the road and saw our house.

You know how, on the news, after a tornado, they always have that helicopter footage? And the helicopter dips low and the camera angle is askew, revealing inconceivable destruction? And you can’t believe your eyes how someplace where life existed just a day before was now such a jumble of ruin, edging into decay? And then the helicopter turns ever so slightly and you see it? That one house that somehow just missed the wrath of the twister? When we turned that bend in our road, that was our house.

It stood, two stories tall, the brick thick with mud, the black wooden shutters still latched tight. Trees down, two feet of finish worn off clean from the formal double front doors where the water lapped up against them for hours. The camellia bushes were barren. The fifty-gallon front porch flowerpots too heavy to move before we left were gone, but otherwise?

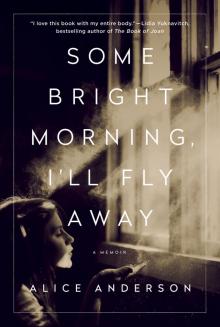

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away