- Home

- Alice Anderson

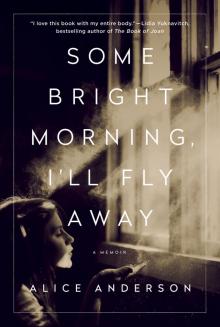

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated to my sweet three, Avery, Grayson, and Aidan, without whom I would not have been able to fly away to such sweet “finally.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my profound gratitude to Jen Gates at Avevitas Creative Management, who saw this book from the first fifty pages to final draft and championed me every step of the way; to Nichole Argyres at St. Martin’s Press, who believed without wavering in this memoir and the poet who wrote it; and to Mira Bartok, Jo-Ann Mapson, Barry Goldstein, Daniel Jensen, the late Stormé Delarverie, the late Norris and Norman Mailer, Stephen King and the Haven Foundation, PEN America, Caroline Leavitt, Luis Alberto Urrea, Lidia Yuknavich, my writing teachers Mark Doty, Jean Valentine, Sharon Olds, Dennis Schmitz, and especially the late Thomas Lux, my mother, Mary Anderson, and, of course, Avery, Grayson and Aidan Anderson.

PROLOGUE

We make chapels of our scars.

They cross our skin and soul, a topographic map of the past. Our scars are built on the delicate yet dazzling scaffolding holding our weary, ragtag hearts aloft. I have in me a scar where my childhood sits, made up of playground songs and the raised-red slap of despair, inside the slate-blue cloudless empty spot between my ribs. In me there is a scar made of Paris nights so bright, plum-black and terrifying, my legs striding cobbled streets toward something, anything, that doesn’t look like disaster. In me I have a wedding scar, pasted on with disappointment, made of that sinking feeling of not knowing if you do, the moment before the moment you are required to say I do, and do. There is a childbirth scar, born of the one who came and left at once in blood and tears—too soon, too soon. There is a father scar, made of terrible nights and resolution and a line of still green trees standing ornate as lace in a grove outside a medical school, where my father gave his body, saying my body for yours: a kind of atonement by tree. And I must admit in me there is a terror scar—it snakes so gingerly around my life entire, barbed and impossible to escape, a battered paper sack of oblivion I carry with me everywhere I go. But there are love scars, too, the most jagged of them all—where one child and another and another and another were born in fire and bliss; where the one whose eyes shone like promise embraced you night after night, sharp kisses holding impossible daylight at bay. Every one of them is a chapel. Every one of them becomes the religion of your life.

We all make chapels of our scars.

PART ONE

SMITHEREENS

HOW I LEARNED TO SHOOT A GUN

Extraordinary things always happen on ordinary days. It was another quiet Mississippi morning, with the acrid scent of debris-pile fires sharp in the humid air. The kids and I were making trips back and forth between the FEMA trailer perched in Mr. Manning’s backyard and the Land Rover when his daughters, Lana and Shelby, showed up and asked the kids if they wanted to go to town for some errands and a treat. Lana was my best friend; Liam had always hated her. With porcelain skin devoid of makeup, a wild head of black curly hair, jeans so tight and tank tops so small, Lana was more ’80s Nagel poster come to life than proper Southern gal.

The kids loved her, and so did I.

These days my sweet three were attached to me like sequins on an opera diva, but Lana and Shelby mentioned going to Tato-Nut (the local doughnut shop in downtown Ocean Springs, where the sinfully hand-fried doughnuts were made of a mashed potato dough), and so the kids eagerly hopped in her van, and it pulled away down the long, red dirt drive.

Mr. Manning, otherwise known to all as “Daddy,” took one look at me standing there in my vintage Wranglers and sleeveless plaid shirt, cocked his eyebrow, and gave me “the look.”

You know: the look. The one your daddy gives before he shoves you off the lake cliff, or guns the boat motor, or buys you your first shot in a dive bar down to Bayou La Batre. Like there’s about to be trouble.

“Welp,” he said, watching the van disappear between the scorched towers of salt pine savanna on either side of Poticaw Bayou Road. “Might as well learn you a bit of something while they’re gone,” he called over his shoulder, heading off in the direction of Lana’s house.

We walked the three or four houses down the street to Lana’s, went through the back door into the mudroom, then the kitchen, where he went about removing all the cereal boxes from the cabinet above the fridge.

“Are we supposed to—?” I started to ask.

“Hush up, now! You think I need permission to be in my own girl’s kitchen?” He laughed.

Then he went about setting four, five, then six, finally nine pistols on Lana’s kitchen counter, all in a row. Now, I’d never touched a gun before, let alone had a row of them lined up before me like new pocketbooks down to the Gautier mall out on Highway 90. We stood there, on opposite sides of Lana’s periwinkle speckled kitchen counter, silent, staring down at the guns. Finally, Daddy broke the ice.

“Which one y’like?” he asked.

I stood looking at them for a bit, momentarily speechless.

“Well?”

“I don’t even, I mean, I’ve never, I guess. Well, are these? I don’t, you know, where did these? Um, did they? I just, it’s just that, I couldn’t, I mean, I can. I just haven’t, or shouldn’t, or, well, you know, I have kids! But I do want to, well, you know. Shoot.”

Daddy laughed at me—hand slappin’ his thighs, turning around in circles, wiping tears from his eyes, trying to speak but falling apart in squawking sounds of total conniption, stomping his boots, and finally (mercifully) resting his head on his arms on the Formica countertop and letting out a big, long, high-pitched sigh.

“Whew, girl! That was the best damn laugh I had since George Bush was on the WLOX changing a porch bulb with that Gautier doctor!”

Well, that got me.

See, after the storm, George Bush caught a lot of grief for being virtually absent from the disaster. He was off doing God knows what all while people tried to rise up from the mud and get their dead cool enough to bury. So before you could drag your party barge off your grandma’s roof, Bush finally decided to do a flyby, past New Orleans, and on down the coast to Mississippi, where it seemed the whole world could not give a good goddamn we’d suffered a direct hit. Grayson and I were folding another load of our neighbor’s clothes we’d done running the washing machine off the generator one day when we heard the unmistakable whap whap whap whap of a helicopter’s propeller cutting through the wet air. We ran out just as it broke across the line of our roof behind us and passed above our heads: I stooped to scoop up Grayson instinctually, all the while hunched over like those blades would cut me down. But to my disappointment, Marine One passed right over us and landed another block down on the lawn of Dr. Jim Bullinger.

Bush stepped out, proceeded to shake hands, survey the swanky, mostly untouched-by-the-storm-surge yard, then stepped up on his porch, media clamoring, to change a bulb.

Meanwhile, folks were waiting for the earth to dry to bury their dead.

“Are you waiting for Jesus’ Second Coming?”

Daddy knocked me back into the reality of that kitchen, and the guns, and how quickly I’d come from there to here.

“I can’t,” I finally announced.

“Yes, you can. And you will. And I’m going to teach you. Pick one.”

There was a big black one that looked heavy as hell; a fancy little one with what appeared to be actual mother-of-pearl inlay that had my name all over it. There was a useful-looking metal number that looked either very professional or as if it were purchased in the “as seen on TV” section. Another had an old-fashioned, tooled Western handle. One was black, one flat gray, nondescript: shiny or not shiny, with smooth surfaces or textured shells.

“Where did y’all get all these?” I asked finally.

“That, my dear, ain’t none of your business,” Daddy scolded, then went about telling me where each and every gun came from and why it would never be able to be traced.

One came from his buddy down the road who bought it from his nephew’s teammate on the football team at Ole Miss. One came from a gun show, where he got a guy to throw it in for free when he made a substantial purchase of a hunting rifle and other various items, after much bargaining. Another came from one of the ladies down to Mac’s Ladies’ Circle Bible Study. One someone in the family got in their stocking from Santa.

“You pick one, whichever one you want. If ever you fire it—provided you hit your man—ain’t nobody ever going to know where the gun come from unless you see fit to say so. And if you do snitch like a damned fool, then I’m going to side with your snake-ass-soon-to-be-ex-husband and say you’re just a Little Miss Nutcase. Got it?”

“Yes, sir,” I whispered, heart beating loudly in my ears like a panicked bird in dark eaves.

“Now, don’t go looking at me like that; y’all know you and your brood are family now, and we’re behind you all the way, and that motherfucker ain’t going to get away with any of this crap, and he sure as shit ain’t going to come back and take up where he left off, and I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t trust you enough not to sell me down south to the fuzz.”

I picked up one of the all-black guns that wasn’t too big, wasn’t too small, and looked like I might be able to handle it. With it cradled in my hands like a scented bouquet, I found myself unable to speak.

“And let me congratulate you, Miss Alice, for havin’ the good sense to pass over that pretty mother-of-pearl pistol that’s got you all aflutter because, A, it can’t shoot worth a damn, and B, it shows you’ve got some jalapeño hush puppies hidden in those Yankee dungarees,” he said, chuckling. “Now, let’s go shoot.”

“Yes, sir,” I whispered, and I followed him out the door.

We walked down the road to the little white house, and he led me about fifty yards northeast of the house, to his shed—a squat, shanty-like structure.

I call it a shed for lack of a better term.

A shed brings to mind a structure for storing a riding mower, or tools, or an old pickup. A shed is a place you shove all your crap in when your garage is full up to the rafters. A shed is where boys go to set things on fire and smoke things their mamas told them not to. A shed is where a girl stashes letters from her secret boyfriend and where a man keeps a lockbox of cash he don’t want his wife to know about.

This was less of a shed, more of a bunker. The walls were made of odd bits of cast-off materials. One wall was the ever-present corrugated tin. Another seemed to be patched-together pieces of an old railroad car or dumpster, with E-N-S-A-C-O-L-A in rusting two-foot-high blue letters stamped across the top. The third was clearly made from wooden privacy fencing. The fourth wall, the one that held the door, was simply a patchwork of varying, mystery rough-hewn odds and ends. The ceiling was low, and Daddy had to stoop a bit as he made his way around in there. Every inch of space was crammed full up with all manner of industrial gadgets and tools, a virtual museum of country manhood.

I’d never been inside there before—never pondered the notion. But I tell you—that place was organized like you wouldn’t believe. There must have been two hundred baby jar lids nailed to one wall, and that many jars again filled with every kind of thing you can (and can’t) imagine a man might have in a shed screwed tight to each lid.

“Now, I’ve had my boys in here and my grandsons once or twice, but none of the girls, not a one, so you’re sworn to silence, hear?” He lowered his eyes at me.

“Right,” I agreed, pretty much along for the ride.

I had the medium-sized, midnight-black, not-too-heavy pistol in my skirt pocket, and I was keenly aware of that side of my body. I felt as if I were standing in one of those trick rooms at an amusement park, the kind that makes you feel like you’re a freakish giant and that the whole earth is tipping and you’re the only thing straining to stand up straight.

“Mac tells me you’re a poet. A real poet,” he said, one ragged eyebrow raised.

I nodded, not sure what he was getting at.

“Well, I didn’t know people could be a real poet anymore, but I guess if there’s still boys that choose to be a priest, there’s likely some crazy girl who’d choose to be a poet, though I don’t know what all kind of job you’d get with that kind of learnin’,” he bantered, almost to himself.

“Yes, sir. I’m not known for my practical side.”

“No matter, girl. Probably the world needs poets, and anyway, that’s what made me decide to bring you in here and show you my bullets.”

“Your bullets, sir?”

“My bullets.” He smiled, that same eyebrow cocked high, nearly raising off the top of his head.

He was enjoying this.

There was a long pause. Dust motes sank in the humid air in the slash of jade light coming through a long stretch of green plastic standing in for a window.

“I make them myself.”

Now, I should say that at this point, I was a girl covered in bruises and knife wounds living in an abandoned FEMA trailer, about to move back into her big, fancy house, whose husband had just been thrown out of his own house by the Jackson County sheriff. I don’t know why standing in a makeshift shed with Daddy about to show me his homemade bullets brought me such an overwhelming sense of serenity, but it did.

In the back corner of the shed were two big drums full of what looked like broken-up pieces of metal about the size of cheese snack crackers. Dirty, grease-smeared metal pieces by the hundreds, maybe thousands. Daddy took a handful from one barrel, walked it back over to me, and threw the pieces down across his worktop like a fistful of dice.

“Any idea what these might be?” he asked.

I picked one up. They were heavy. Cold. Pale silver, with a bit of patina. Rough at the edges where they’d been broken up in chunks.

“Look closer,” he urged.

I had no idea.

“C’mon, girl! Take a guess!” he urged.

I picked up a few more, held them up in the bottle-green, tropical air. Each piece had what looked like a reversed word or part of a word on it, raised metal text. Daddy chuckled when he saw me starting to figure it out.

“Typewriters?” I ventured.

“Do typewriters come with whole words on the keys, Miss Smarty Poet Yankee Doodle Girl College?” Apparently, news had gone around I’d gone to Sarah Lawrence.

“No, sir,” I mumbled, trying to read the words, having figured out at this point that most of the words were broken into pieces but that a few of the little metal chunks held at least one complete word or two, such as the following d or rd and hen day if you could remember to read them backward.

“Printing press, girl! It’s from a printing damn press!” he shouted.

Then he told me where he had gotten these drums of printing press pieces, and he also explained to me how he heated them up, mixed them with Lord knows what all else, mashed them into little

bullet molds, and turned them into his very own, homemade bullets, but in all honesty, I can barely remember a word of that part of the story.

I was having a moment—one of those destinations in time where you arrive and it seems the world is made for you. Some call it fate, others coincidence. To me, it’s poetry: something I recognize in the world and feel in my soul.

Here I was, a girl whose husband had nearly killed her, a husband who had forbidden her years before from ever writing another poem, standing in a shed in unincorporated Latimer, Mississippi, with an untraceable pistol in her pocket and a barrel of broken-up stories sitting ready to be transformed into ammunition in the corner, waiting on getting her first lesson on how to shoot a gun.

He gave me a handful of bullets for my other pocket.

“C’mon,” he said, “there’s only so many Tato-Nuts them little rug rats can scarf.”

We went through the garden patch and cut north toward the pond to a stand of trees in an otherwise elegant, silent clearing. There was a battered folding table out there, and a pile of newspapers underneath with a big rock on top to keep them from taking flight like seabirds. Daddy took a paper off the stack, walked into the grove, opened up the paper, folded it back again to expose a page with a big picture of some smiling politician with his hand up in the air in a sign of victory. Daddy brought a small hammer and a tack out of his pocket, nailed the page to a tree, and walked back to me.

“Hold it up like this,” he said, coming behind me, grabbing my arms, putting me in place to shoot the gun. “Choose a target in the picture, find it, mark it, take a deep breath. And when you’re ready—shoot,” he whispered, his breath hot in my ear.

It was quiet.

About three seconds passed.

I pulled the trigger.

The sound was a shock. I didn’t fall back; didn’t drop the gun. The paper fluttered.

“Damn!” yelled Daddy, running across the field to the paper, still tacked to the tree. “Woo-hoo, girlie! You hit it, pre’near almost hit the target! You hit his hand.”

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away

Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away